Most people in the sheep industry are probably aware of the changing landscape of both this commodity and all of agriculture. Producers have more marketing options than ever before; currently, non-traditional markets make up 30% of sheep sales in the U.S. On the retail side, there are grocers committed to selling either exclusively or partially American lamb; some have even started in-store American lamb branded campaigns. While lamb consumption is seen most on the coasts, popularity is increasing in large metropolitan areas. Producers have historically been able to generate a strong holiday-oriented supply of lamb, but a year-round supply is needed for consistency in both traditional and non-traditional markets.

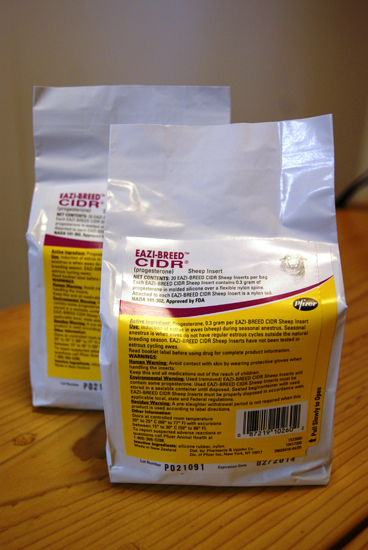

As a result of inconsistent supply, “there are wide monthly fluctuations in both the numbers of lambs available and in the prices received by producers,” the 2010 proceedings “Out-of-Season Breeding Using the EAZI-Breed CIDR-G in Ewes,” by Dr. Keith Inskeep, Dr. Marlon Knights and Todd Ramboldt, graduate research assistant in reproductive physiology, West Virginia University-Morgantown, say.

“These seasonal lambing periods can affect prices since many producers are marketing lambs at the same time of year. Further, the inconsistent supply reduces the efficiency of lamb processors and results in periods of low availability to the consumer.”

Increased demand for a consistent supply of lamb has led to accelerated lambing systems, out-of-season breeding and condensed lambing periods. To accommodate these production tactics, some producers have included sheep CIDRs (Controlled Intravaginal Drug Release) as a regular component to their breeding protocols. Estrus synchronization is one of the single best ways for producers to accomplish the goal of year-round supply; it also saves labor and increases ewe receptivity to artificial insemination (AI). “Synchronized breeding leads to synchronized lambing, thus concentrating and reducing the labor requirement at lambing,” the proceedings explain. A uniform lamb crop, due to breeding and lambing synchronization, facilitates an advantage when marketing lambs because of reduced age and weight breaks.

Approved for use in sheep in October 2009, CIDRs are used for synchronization of estrus resulting in out-of-season breeding and larger groups of ewes that can be bred at the same time in order to narrow lambing periods. CIDRs deliver progesterone to a ewe in response to the introduction of a ram. Progesterone is a steroid hormone naturally produced by the corpus luteum of mammalian ovaries; it diffuses through the cell membrane and the nuclear membrane, binding to the progesterone receptor in the nucleus, thus causing a change in cell physiology. In vivo, progesterone functions to maintain pregnancy and provides a potent suppression of estrus, making it important for estrus synchronization in animals.

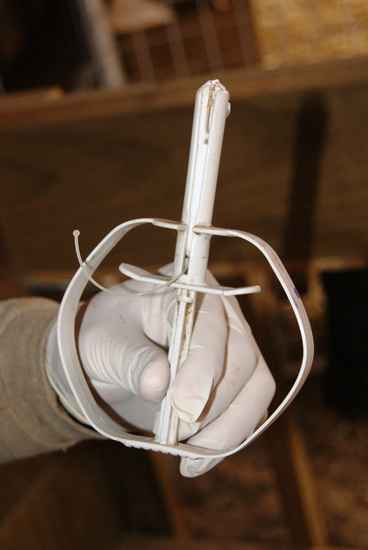

A CIDR, according to www.ansci.wisc.edu, is a T-shaped nylon insert molded with a silicone rubber skin containing progesterone that’s released at a controlled rate into the bloodstream after insertion; sheep CIDRs contain 0.3g progesterone per insert. Progesterone is released from the skin of the insert, causing the animal’s blood progesterone concentrations to increase rapidly; maximum concentrations are reached within an hour after insertion. After CIDR removal, a rapid drop in concentration of systemic progesterone occurs, thus promoting a synchronized estrus effect within a flock, allowing for natural breeding or AI to take place.

A CIDR, according to www.ansci.wisc.edu, is a T-shaped nylon insert molded with a silicone rubber skin containing progesterone that’s released at a controlled rate into the bloodstream after insertion; sheep CIDRs contain 0.3g progesterone per insert. Progesterone is released from the skin of the insert, causing the animal’s blood progesterone concentrations to increase rapidly; maximum concentrations are reached within an hour after insertion. After CIDR removal, a rapid drop in concentration of systemic progesterone occurs, thus promoting a synchronized estrus effect within a flock, allowing for natural breeding or AI to take place.

CIDR insert up close.

The wings of a CIDR, the website continues, fold together for intravaginal insertion. Once inserted, the wings return to their original T-shape and apply pressure to the vaginal walls, thereby holding the CIDR in place. CIDRs are removed following the treatment period of 12 to 14 days by simply pulling the plastic tail protruding from the vulva.

To insert a CIDR, first restrain the animal and then clean the area of the vulva thoroughly. Put the body of the insert into the applicator, with the tail in the slot. Apply lubricant to the tip of the insert and position the insert with the tail on the underside of the applicator, curling down. Open the labia and slide the applicator in at a slight upward angle, then depress the plunger and withdraw the applicator slowly. To remove, pull gently on the tail and dispose properly. For best results, wash the applicator with disinfectant between uses. CIDRs cost about $6 each; applicators $10 each. Both items can be found at www.premier1supplies.com.

Put the body of the insert into the applicator, with the tail in the slot. See next photo.

Place CIDR insert into the applicator.

Lubricate the insert and applicator.

Open the labia and slide the applicator in at a slight upward angle.

Depress the plunger and withdraw the applicator slowly.

A properly placed insert looks like this.

Since there is some cost and labor associated with use of sheep CIDRs, some producers may be asking themselves, “Why would I want to use CIDRs?” First and foremost, according to Dr. Inskeep, CIDRs are a tool for breeding out-of-season. Goals for changing breeding – and, coincidently, lambing – seasons are for improved prices, fewer losses to predators and lower feed costs – all things that add up to improved profitability. Further, CIDRs result in higher conception rates during the first service, increased value from semen due to a higher success rate of AI and exact breeding dates.

We’ve learned that a CIDR functions to deliver progesterone to the ewe, but the most important thing, Dr. Inskeep says, is that this prepares her to show estrus and ovulate in response to introduction of the ram. CIDRs are effective in mature ewes in good body condition that aren’t lactating and have been isolated from the ram for at least a month prior to breeding for optimum results. The ewe to ram ratio when using CIDRs is recommended at 18:1. “Ram lambs and yearling rams performed equally in three ram lots and could handle 18 ewes per ram,” Dr. Inskeep reported at the National Sheep Symposium held in July 2012. “In single ram lots, ram lambs were less able to service 18 ewes than yearling rams,” he continued. “Even yearling rams had less success with 18 than with 12 ewes in single ram lots.”

Another factor when considering use of CIDRs is the length of breeding season of the sheep. Breeds with short breeding season lengths include Southdown, Cheviot and Border Leicester. Hampshire and Suffolk sheep are generally considered to have intermediate breeding season lengths, while Dorset, Rambouillet, Merino and Finnsheep have long breeding seasons. Year-round breeding seasons are associated with Katahdin, Barbados Blackbelly and St. Croix sheep. Length of breeding season heritability is estimated at about 26%, Dr. Inskeep said, which is greater than most reproductive traits. An especially important take-home message, Dr. Inskeep reported that if producers keep fall-born replacements, they’re selecting for responsiveness to CIDRs plus ram introduction. Still, Dr. Inskeep said to keep in mind that in studies ewe lambs and lactating ewes didn’t respond well to out-of-season breeding even with the use of a CIDR.

Whether synchronizing ewes for an AI date, to breed out-of-season or to tighten lambing seasons, CIDRs are highly likely to help accomplish flock goals.