COOP SECURITY

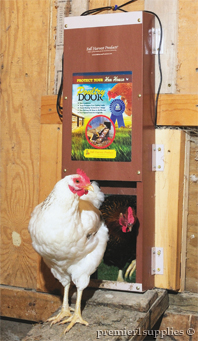

Premier's hens kindly demonstrating the ins and outs of the Poultry Door.

NEW! Incredible Poultry Door™

Allows birds to be outside during the day even when you’re not around to open/close their door.

| • |

Uses a daylight sensor to open at dawn and close at dusk—automatically. |

| • |

Keeps predators out and chickens safe inside when door is closed. |

| • |

Easy installation. |

| • |

Raccoon-proof screw-drive design. |

| • |

No cables or jam-prone traction doors. |

| • |

Safety feature—auto-reverses upon jamming or closing on a bird. |

FENCE SOLUTIONS FOR POULTRY, DUCKS & GEESE

Installing PoultryNet 12/48/3 to contain poultry in a pasture previously grazed by sheep.

What is poultry netting?

An electrifiable, prefabricated, portable fence. Arrives as a complete fence (except for an energizer and lightweight corner posts) with line posts built into each roll.

We use it extensively on our farms for managing our poultry.

Fencing an area with multiple curves and corners?

Consider using PoultryNet™ Plus and PermaNet® Plus nets. The added posts provide increased support and help in reducing potential sagging.

PoultryNet™ 12/42/3

| • |

To contain and control the movement of chickens, ducks and other poultry. |

| • |

To prevent raccoons, coyotes, foxes, dogs, bears and other nonflying predators from killing poultry. |

| • |

To rotate poultry to fresh grass and to reduce disease risks. |

PoultryNet™ 12/48/3

| • |

To contain and control the movement of chickens, ducks and other poultry. |

| • |

To prevent raccoons, coyotes, foxes, dogs, bears and other nonflying predators from killing poultry. |

| • |

To rotate poultry to fresh grass and to reduce disease risks. |

PermaNet® 12/48/3

| • |

Boundary fence. |

| • |

Subdivision fence. |

| • |

Keep in/out all nonflying poultry. |

| • |

Keep out nonflying predators. |

To help simplify your purchasing decisions, you can order a PoultryNet 12/42/3 kit or a PoultryNet 12/48/3 kit.

Remember to electrify the netting. Our energizer kits simplify this purchasing decision also.

PREMIER ENERGIZERS

Domestic turkeys fenced in and protected by PoultryNet™ 12/48/3 energized with a PRS energizer. If your birds are a breed that likes to fly, make sure to clip their wings to discourage them from flying out of paddocks.

Which unit is right

for you?

The size, in pulse energy output (range from .5 joule to 2 joules), depends almost entirely on the weed contact that will occur and the length of the fence.

Contact Premier or call 800-282-6631 to speak with one of our fence consultants to help you determine the best energizer for your needs.

You can also view our energizer comparison charts online or in Premier's fencing catalog for help in choosing an energizer.

If it's the beginning of your fencing season, you'll find our video above on how to get your PRS Solar Energizer ready for fencing season helpful, with instructions and tips the folks at Premier have learned by experience.

|

|

|

A side-by-side comparison of PoultryNet™ Plus 12/42/3, green and white. The green netting "disappears" (which many prefer) in a green pasture, even with its single green/white horizontal strand for night visibility. The white netting is far more visible both day and night.

Winter is almost over!

Winter hasn't been too horrible—aside from wrestling with cold spells and frozen waterers. But the kicker is our hens have drastically reduced their egg production during the cold, dark weeks. The few eggs that we have received are often "frosty" or even frozen. (Sometimes it's been so cold we're not sure if the egg-freezing occured before or after the egg was laid!) Fortunately the cold spells that caused most of these issues has passed. That and the hours of available sunlight is slowly—but surely—increasing. So we should see an increase in egg production any day now, fingers crossed.

The downside is poultry predators will be on the move now that they don't have to venture out into subzero chill. We'll have to be onguard to make sure foxes, raccoons and other predators stay far away from our coop.

Below are a few articles for late winter reading.

EXTENSION NEWS

Rearing chicks and pullets for the small laying flock

By Melvin L. Hamre

former Extension Animal Scientist Department of Animal Science

Copyright © 2013 Regents of the University of Minnesota.

All rights reserved.

Good layers develop from healthy, well-bred chicks raised under good feeding and management programs. Buying the right type of chick is important for the most economical production. The best hens for egg production are the small-bodied commercial White Leghorn strains with a high rate of egg production that yields a lower production cost per dozen eggs. Some commercial brown egg-laying strains are now available that lay nearly as well as White Leghorns and are satisfactory for small-flock production. Consider raising both some good egg-type pullets and some broiler crosses for meat, rather than trying to use a dual-purpose breed that isn't best for either purpose.

Producers should order sexed pullet chicks when purchasing egg-production strains. Males are not needed in an egg production flock unless fertile eggs are wanted for hatching. The males eat feed and take up space that could be used by hens. There are commercial hatcheries and jobbers in most areas of the state that are able to provide good healthy chicks or pullets of the egg-laying strains.

It's best to delay the sexual maturity of pullets to permit better body growth before they begin egg production. An increase in daylength encourages early sexual maturity of the pullet. Chicks hatched between April and August can be exposed to the natural daylength because the daylength is decreasing during the latter part of the growth period. These birds will respond favorably to increased light stimulation when they are physically ready to come into production. Producers with small flocks should consider starting chicks after March, since less heat will be required to brood them.

Economic Considerations

You may be better off buying started pullets. Compare your costs to dealer prices. Figure the costs of raising a started pullet under your conditions. Multiply your chick cost by 1.1 to allow for some mortality and culling. Leghorn pullets will eat from 16 to 18 pounds per bird and heavy breeds will eat from 20 to 22 pounds from hatch to 20 weeks of age. Figure any equipment costs depreciated over a 10-year period and housing costs over a 20-year period if expenses are incurred. Estimate your expenses for litter, heat for brooding, lights, medication, and other miscellaneous production costs. Allow for any payments made for labor to care for the flock. Convert your figure to a per-pullet basis for comparison.

Housing and Equipment

Housing requirements for brooding and rearing chicks and pullets can be quite minimal if done in late spring and summer. Almost any small building that meets the floor-space requirements for the desired-size flock can be used. A small number of chicks can even be brooded in a corner of a garage. After the brooding period, pullets can be reared in a fenced range or yard with only a covered shelter for protection from the weather.

Read More »

EXTENSION NEWS

Evaluating egg laying hens

By Jacquie Jacob, Tony Pescatore and Austin Cantor

University of Kentucky, College of Agriculture

Also see us at www.eXtension.org/poultry or our facebook page

Most flocks of egg laying hens go through the same typical production curve. As shown in Figure 1 (see pdf below), the flock quickly peaks in egg production and then slowly reduces its level of egg production.

It is important to remember, however, that not all the hens in a flock will be laying at the same rate. Some hens may never lay a single egg while others may go out of production earlier than the majority of the flock. Economically it would be helpful to find such hens and remove them from the flock. To do so requires an ability to assess the persistency and intensity of lay for each hen. Persistency of lay refers to the number of eggs laid over a specific period of time. Intensity of lay refers to the current level of egg production.

With yellow-skinned hens, such as leghorns, loss of pigment from their skin is an important characteristic for determining the persistency of lay. As a pullet grows, yellow pigment is deposited in the skin, beak, shanks and feet. Once the pullet starts laying eggs, the pigment is then removed from the pigmented areas to provide the yellow color in egg yolks.

The pigment is removed from the different parts of the body in a definite order - from the vent, eye ring, ear lobe, beak (corner of the mouth toward the tip), bottom of the foot, the shank (front, back and sides) and finally the hock and top of toes (see Figure 2 (see pdf below) for the parts of the hen).

Once a hen stops laying eggs, pigment is regained to the skin in the same order in which it was bleach. It is NOT regained in the reverse order.

As previously indicated, the first place to loose pigment is the vent. A hen that has been producing eggs will have very little yellow remaining in the skin around the vent. As shown in Figure 3 (see pdf below), the hen on the left still has yellow remaining in the vent. She has either laid few, if any eggs, or has been laying eggs and has gone out of production, putting pigment back into the vent (since pigment is replaced in the same order it was removed). The vent of the hen on the right has been bleached of pigment indicating she has laid more eggs and is therefore the more persistent layer.

As shown in Figure 4 (see pdf below), there is no yellow pigment remaining in the eye ring, ear lobe and beak of a hen that has been in production. Yellow pigment is present in all parts of a poor layer’s head. In addition to differences in pigmentation, the comb of the poor layer is smaller and pale. The head is also too long in proportion to its depth.

Read More »

PREDATOR TIPS

Getting along with predators

The following article was originally published in the June/July 2012 issue of Backyard Poultry Magazine. Note that the two sidebars in that article I am here presenting in separate pages, as “The Usual Suspects” and “Purchased Aids for Predator Defense”.

Added to the site November 20, 2013.

Table of Contents for This Page

| • |

Predators in the Neighborhood Ecology |

| • |

Fortress Gallus |

| • |

Protecting Ranging Poultry

|

| • |

Aerial Predators

|

| • |

Pets as Predators

|

| • |

The Rogue Predator |

| • |

Final Thoughts |

There are any number of neighbors in our local ecology that are tolerable in moderate numbers but whose reproductive powers are awesome, and whose populations explode to catastrophic levels absent some sort of check. If you’ve had problems with rabbits or voles in your garden or mice in the henhouse, imagine a population level ten or a hundred times anything you’ve seen to date. Imagine the devastation to garden and orchard if crop-damaging insect populations soar. Imagine losses in your flock if weasels and minks were around in abundance. Fortunately we have some excellent partners to help keep some sanity in the neighborhood free-for-all: predators.

Predators in the Neighborhood Ecology

Too often our response to predation threats to our poultry is a shoot-from-the-hip assumption that the obvious solution is to kill the predators. If we appreciate the critical roles predators play in our local ecology, however, we will honor them and respect their access to habitat in which they can range to fulfill those roles. Of course, the efforts we make to nurture our flocks for matchless eggs and dressed poultry for our families would come to naught if predators have easy access to our birds. The obvious compromise strategy is: The best offense is a good defense.

Our notions of what predators eat lean toward the dramatic: They feast on animals of most interest to us—lambs, calves, piglets. Chickens. Turkeys. The truth, more prosaically, is that the most important foods for most predators likely to prey on your flock are precisely the animals mentioned above: rabbits, insects, and rodents. Long before your poultry moved into their neighborhood, skunks and opossums and raccoons fed themselves largely on insects and rodents. We think of fox and hawk as the quintessential poultry predators, but my natural history guide deems the fox “probably the world’s greatest destroyer of mice,” while many species of hawks specialize in rodents and rabbits—and some feed on insects as well. Owls prey on rabbits and rodents—and the larger species take minks and weasels. Coyotes eat more rabbits and rodents than sheep and goats—or poultry.

If you find these thoughts on the positive roles of predators hopelessly idealistic and believe that shoot-from-the-hip is precisely the practical solution of choice, reflect on some of the real-world problems with “going on the warpath”: Killing a predator does not solve the problem of predation, it simply opens up its territory for a new claimant—and the warpath solution has to be brought to bear on it in turn. Sounds like an exercise in futility to me.

Note as well that a new claimant to that territory hasn’t had the experience of being defeated by your defensive measures, and hence may be even more likely to get lucky and make a hit. For example, when I put up a wire enclosure for my shredder-composter chickens to work in, a fox tried to dig its way in—once. When it hit the wire barrier I had dug in, it never bothered with another attempt. I often see a fox ignoring my chickens as it trots by their electronet perimeter—clearly it has been well instructed by the demon in my fence. Which fox would I prefer in my neighborhood: the one who has learned not to bother probing my defenses, or a new claimant to an empty territory who certainly will probe—and perhaps find an overlooked opening in the wire, or arrive when there’s a short in the electronet?

Practice defense by preference, and be assured that predators are not stupid: If they have tried to get past your defenses and been frustrated, they will not keep wasting their time on a lost cause—but will go hunting mice or rabbits instead.

Fortress Gallus

The most significant consideration as you plan your defenses is the fact that most wild predators are nocturnal by preference. However freely you range your flock in the day, therefore, make sure to shut them up every night inside a shelter that is absolutely secure against predators. Make their roosting quarters “Fortress Gallus” and you will prevent most nighttime losses.

Read More »

This article is Copyright by Harvey Ussery and reprinted with permission. Harvey Ussery is the author of The Small Scale Poultry Flock (Chelsea Green, 2011), on sale in Premier's book section. Visit Harvey's website at www.themodernhomestead.us.

|

|